Biomarker Testing for Multiple Sclerosis and Related Neurologic Diseases - CAM 324

Description

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is the most common immune-mediated inflammatory demyelinating disease of the central nervous system (CNS) and is defined by multifocal areas of demyelination with loss of oligodendrocytes and astroglial scarring. The most commonly present symptom is sensory disturbances, followed by weakness and visual disturbances. However, the disease has a highly variable pace and many atypical forms (Olek, 2024a). Besides MS, acute CNS demyelination also occurs in acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM), optic neuritis, transverse myelitis, and neuromyelitis optica (Lotze, 2024).

Neuromyelitis optica and neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders (NMOSD) are inflammatory disorders of the CNS characterized by severe, immune-mediated demyelination and axonal damage predominantly targeting the optic nerves and spinal cord. Previously considered a subset of MS, this set of disorders is now recognized as its own clinical entity with its own unique immunologic features (Glisson, 2024).

Regulatory Status

A search on the FDA website on July 14, 2021, yielded no results for “myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein,” “oligoclonal band,” or “neurofilament light chain.” A search on the FDA website on the same date for “aquaporin-4” yielded one result, the KRONUS Aquaporin-4 Autoantibody (AQP4Ab) ELISA Assay. The indication for use is as follows: “The KRONUS Aquaporin-4 Autoantibody (AQP4Ab) ELISA Assay is for the semi-quantitative determination of autoantibodies to Aquaporin-4 in human serum. The KRONUS Aquaporin-4 Autoantibody (AQP4Ab) ELISA Assay may be useful as an aid in the diagnosis of Neuromyelitis Optica (NMO) and Neuromyelitis Optica Spectrum Disorders (NMOSD). The KRONUS Aquaporin-4 Autoantibody (AQP4Ab) ELISA Assay is not to be used alone and is to be used in conjunction with other clinical, laboratory, and radiological (e.g., MRI) findings.”

Additionally, many labs have developed specific tests that they must validate and perform in house. These laboratory-developed tests (LDTs) are regulated by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) as high-complexity tests under the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments of 1988. As an LDT, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration has not approved or cleared this test; however, FDA clearance or approval is not currently required for clinical use.

Policy

Application of coverage criteria is dependent upon an individual’s benefit coverage at the time of the request.

- For the diagnosis of multiple sclerosis (MS), cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and serum oligoclonal band analysis is considered MEDICALLY NECESSARY in any of the following situations:

- For individuals with atypical clinical, laboratory, or imaging features.

- For individuals with an atypical, clinically isolated syndrome, including, but not limited to, primary progressive multiple sclerosis or relapsing-remitting course.

- For individuals belonging to a population in which MS is less common (e.g., children, older individuals).

- For individuals with insufficient clinical or imaging evidence for diagnosis.

- In cases of suspected neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders (NMOSD) or myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein-immunoglobulin G (MOG-IgG)-associated encephalomyelitis (MOG-EM), serum indirect fluorescence assay or fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) assay of aquaporin-4-IgG (AQP4-IgG) and MOG-IgG is considered MEDICALLY NECESSARY when all of the following conditions are met:

- The individual has monophasic or relapsing acute optic neuritis, myelitis, brainstem encephalitis, encephalitis, or any combination thereof;

- The individuals have radiological or electrophysiological findings compatible with central nervous system (CNS) demyelination;

- The individual has at least one of the following:

- Belongs to a higher risk population (e.g., pediatric).

- Has an abnormal MRI depicting extensive optic nerve lesion, extensive spinal cord lesion or atrophy, or large confluent T2 brain lesions.

- Has prominent papilledema/papillitis/optic disc swelling during acute optic neuritis.

- Has neutrophilic CSF pleocytosis.

- Has a histopathology finding of primary demyelination with intralesional complement and IgG deposits or has a previous diagnosis of “pattern II MS”.

- Has simultaneous bilateral acute optic neuritis.

- Has a severe visual deficit or blindness in one or both eyes during or after acute optic neuritis.

- Has severe or frequent episodes of acute myelitis or brainstem encephalitis.

- Has permanent sphincter and/or erectile disorder after myelitis.

- Has a previous diagnosis of acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM).

The following do not meet coverage criteria due to a lack of available published scientific literature confirming that the test(s) is/are required and beneficial for the diagnosis and treatment of an individual’s illness.

- In all other situations, serum biomarker tests for multiple sclerosis are considered NOT MEDICALLY NECESSARY.

- ELISA, Western blot, immunohistochemistry, or any other serum assays to test for NMOSD or MOG-EM is considered NOT MEDICALLY NECESSARY.

- For the diagnosis of MS, NMOSD, or MOG-EM, all other cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) biomarker tests, including AQP4-IgG or MOG-IgG, is considered NOT MEDICALLY NECESSARY.

Table of Terminology

| Term |

Definition |

| ADEM |

Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis |

| AQP4Ab |

Aquaporin-4 autoantibody |

| AQP4-IgG |

Aquaporin-4-immunoglobulin G |

| AQP4-ON |

Aquaporin-4 immunoglobulin G-Associated ON |

| BMI |

Body mass index |

| CBA |

Cell-Based immunofluorescence assay |

| CHI3L1 |

Chitinase3-like1 |

| CIS |

Clinically isolated syndrome |

| CLIA ’88 |

Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments of 1988 |

| CMS |

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services |

| CNS |

Central nervous system |

| CPT |

Current procedural terminology |

| CSF |

Cerebrospinal fluid |

| EDSS |

Expanded disability status scale |

| ELISA |

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent immunoassay |

| FACS |

Fluorescence-activated cell sorting |

| FDA |

Food And Drug Administration |

| GCIPL |

Ganglion cell + inner plexiform layer |

| GEL |

Gadolinium-enhanced lesions |

| HCLA |

High-contrast letter acuity |

| IPND |

International Panel on MOG Encephalomyelitis |

| IVIG |

Intravenous immunoglobulin treatment |

| LDTs |

Laboratory-developed tests |

| miRNA |

Micro ribonucleic acid |

| MOG |

Myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein immunoglobulin G |

| MOG-EM |

Myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein-immunoglobulin G-associated encephalomyelitis |

| MOG-IgG |

Myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein-immunoglobulin G |

| MOG-ON |

Myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein-immunoglobulin G-associated ON |

| MRI |

Magnetic resonance imaging |

| mRNA |

Messenger ribonucleic acid |

| MS |

Multiple sclerosis |

| MS-ON |

Multiple sclerosis-associated ON |

| NfL |

Neurofilament light |

| NICE |

|

| NMO |

Neuromyelitis optica |

| NMOSD |

Neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders |

| OCBs |

Oligoclonal immunoglobulin G Bands |

| ON |

Optic neuritis |

| PPMS |

Primary progressive multiple sclerosis |

| rON |

Recurrent optic neuritis |

| RRMS |

Relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis |

| sNfL |

Serum neurofilament light chain |

| SPMS |

Secondary progressive multiple sclerosis |

Rationale

In the United States, the 2023 estimated prevalence of multiple sclerosis (MS) is 288 per 100,000 individuals, totaling 913,925 persons with MS (Atlas of MS, 2023). The mean age of MS onset is 28 to 31 years of age with clinical disease usually becoming apparent between the ages of 15 to 45 years, though in rare instances, onset has been noted as early as the first years of life or as late as the seventh decade (Goodin, 2014). Prevalence of MS is highest in the 55- to 65- year age group (Wallin et al., 2019).

In most, but not all, cases, a patient presents with a clinically isolated syndrome (CIS) as the first single clinical event. This CIS preludes a clinically definite MS (Lublin et al., 2014). The pattern and course of MS is then further categorized into several clinical subtypes (Lublin et al., 2014): Relapsing-remitting MS (RRMS), secondary progressive MS (SPMS), and primary progressive MS (PPMS). RRMS is the most common type of disease course (85 to 90 percent of cases at onset (Weinshenker, 1994)) and is characterized by clearly defined relapses with full recovery, or with sequelae and residual deficit upon recovery. The transition from RRMS to SPMS usually occurs 10 to 20 years after disease onset (Eriksson et al., 2003). SPMS is characterized by an initial RRMS disease course followed by gradual worsening with or without occasional relapses, minor remissions, and plateaus. PPMS is characterized by progressive accumulation of disability from disease onset with occasional plateaus, temporary minor improvements, or acute relapses still consistent with the definition. A diagnosis of PPMS is made exclusively on patient history: there are no imaging or exam findings that distinguish PPMS from RRMS. PPMS represents about 10 percent of MS cases at disease onset (Koch et al., 2009; Olek, 2024a). Worsening of disability due to MS is highly variable. The impact of MS varies according to several measures, including severity of signs and symptoms, frequency of relapses, rate of worsening, and residual disability. Worsening of disability over time is a critical issue for MS patients (Olek, 2024a). Current treatments can delay the progression of the disease. However, this delay is only achievable if treatment starts at the beginning of the disease. Thus, it is essential that a proper diagnosis is made as early as possible, allowing for early treatment and as much delay as possible in symptom progression (Sapko et al., 2020).

Multiple sclerosis is primarily diagnosed clinically. The core requirement for the diagnosis is the demonstration of central nervous system lesion dissemination in time and space, based upon either clinical findings alone or a combination of clinical and MRI findings. The history and physical examination are most important for diagnostic purposes. MRI is the test of choice to support the clinical diagnosis of MS (Filippi & Rocca, 2011). The McDonald diagnostic criteria include specific MRI criteria for the demonstration of lesions dissemination in time and space; however, the McDonald criteria are not intended for distinguishing MS from other neurologic conditions (Brownlee et al., 2017). The sensitivity and specificity of MRI for the diagnosis of MS varies widely in different studies. This variation is probably due to differences among the studies in MRI criteria and patient populations (Offenbacher et al., 1993; Schaffler et al., 2011). Using the 2010 McDonald criteria, the sensitivity and specificity were approximately 53 and 87 percent, respectively (Rovira et al., 2009). In the first studies applying the 2017 criteria (Hyun et al., 2018), the sensitivity is higher (83.6%), but the specificity is lower (85%).

Qualitative assessment of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) for oligoclonal IgG bands (OCBs) using isoelectric focusing can be an important diagnostic tool when determining a diagnosis of MS. Elevation of the CSF immunoglobulin level relative to other protein components is a common finding in patients with MS and suggests intrathecal synthesis. The immunoglobulin increase is predominantly IgG, although the synthesis of IgM and IgA is also increased (Olek, 2024a). A positive finding is defined by “finding of either oligoclonal bands different from any such bands in serum, or by an increased IgG index” and can be measured by features such as percentage of total protein or total albumin. Up to 95% of clinically definite MS cases will have these oligoclonal bands (Olek, 2024b).

The 2017 McDonald criteria allows for the presence of CSF oligoclonal bands to substitute for the diagnostic requirement of fulfilling dissemination in time. However, Thompson notes that “currently, no laboratory test in isolation confirms the diagnosis of multiple sclerosis” (Thompson et al., 2018). Luzzio (2023) also note that in a review of four guidelines from the Consortium of Multiple Sclerosis Centers, the European Academy of Neurology, and the Magnetic Resonance Imaging in MS Network, MRI is the “imaging procedure of choice for confirming MS and monitoring disease progression in the brain and spinal cord” (Luzzio, 2023).

Neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders (NMOSD, also known as Devic disease or neuromyelitis optica, NMO) are a range of conditions that are characterized by symptoms similar to MS; namely demyelination and axonal damage to structures of the central nervous system, such as the spinal cord. Previously, NMOSD were considered a subset of MS; however, now NMOSD and NMO are recognized as having distinct features, specifically the presence of a NMOSD/NMO-specific antibody that binds aquaporin-4 (AQP4), setting these apart from relapsing-remitting MS. AQP4 is a water channel protein primarily located in the spinal cord gray matter. NMO-IgG (or anti-AQP4) is involved in the pathogenesis of NMOSD/NMO. This antibody selectively binds AQP4, differing from MS in that the loss of AQP4 expression is unrelated to the stage of demyelination. The presence of this antibody is incorporated into the current diagnostic criteria for NMOSD and can differentiate MS cases from NMOSD cases (Glisson, 2024).

Several novel MS-related prognostic biomarkers are being investigated for clinical use. Serum neurofilament light chain (sNfl) has been implicated as a potential marker; however, it is clinically difficult to evaluate individual patients with NfL because of confounding variables; NfL can indicate neuroinflammation (rather than neurodegeneration). Other biomarkers of axonal damage, neuronal damage, glial dysfunction, demyelination, and inflammation are beset by similar issues as well as limited by conflicting results from studies. According to Yang et al. (2022), future practice could benefit from integrating a diverse set of biomarkers (a combination of proteins, transcriptomics, immune cells, extracellular vessels, metabolites, and the microbiome). Scientists could use cutting-edge bioinformatics to identify and predict disease progression. Other promising technologies may aid in the discovery of new biomarkers such as proteomics, metabolomics, and sc-RNA seq (Yang et al., 2022).

Clinical Utility and Validity

There is a strong unmet clinical need for objective body fluid biomarkers to assist early diagnosis and estimate long-term prognosis, monitor treatment response, and predict potential adverse effects in MS. Currently, no biomarkers of MS have been validated; however, many are under consideration: microRNA (miRNA), messenger RNA (mRNA), lipids, autoantibodies, metabolites, and proteins all have been reported to have potential as possible biomarkers (Comabella & Montalban, 2014; Comabella et al., 2016; El Ayoubi & Khoury, 2017; Lim et al., 2017; Raphael et al., 2015; Teunissen et al., 2015).

Fryer et al. (2014) compared three assays for measuring aquaporin-4 IgG: ELISA, fixed cell-based fluorescence (CBA), and live cell-based fluorescence (FACS, M1 and M23 versions). Four groups of patients were measured with these assays. In Group one (n = 388), FACS was optimal, with the highest area under the curve. In Group two, FACS identified the highest percentage of neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders, identifying 23 (M1) and 24 (M23) of 30 patients. In Group three, all four assays identified true negatives at an approximate 85% success rate (5 of 31 positives). In Group four, all four assays identified true positives in 40 of 41 samples. The authors noted that “aquaporin-4-transfected CBAs, particularly M1-FACS, perform optimally in aiding NMOSD serologic diagnosis” (Fryer et al., 2014).

Jitprapaikulsan et al. (2018) evaluated the prognostic value of aquaporin-4 IgG and myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein IgG (MOG) in patients with recurrent optic neuritis (rON). The study included 246 and autoantibodies were detected in 32% of these patients (aquaporin-4 in 19%, MOG in 13%), 186 patients had rON only and 60 patients had “additional inflammatory demyelinating attacks” (rON plus). Of the 186 rON only patients, 27 were positive for MOG, 24 were positive for aquaporin-4, and 110 were negative for both. In the rON plus group, 23 were positive for aquaporin-4, 4 were positive for MOG, and 11 were negative for both. The authors noted that five years after optic neuritis onset, 59% of aquaporin-4 positive patients and 12% of MOG positive patients were estimated to have “severe visual loss”. The authors concluded that “aquaporin-4 IgG seropositivity predicts a worse visual outcome than MOG IgG1 seropositivity, double seronegativity, or MS diagnosis. Myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein IgG1 is associated with a greater relapse rate but better visual outcomes” (Jitprapaikulsan et al., 2018).

Sotirchos et al. (2019) compared 31 healthy controls with individuals with one of three types of optic neuritis (ON): 48 individuals with aquaporin-4 IgG-associated ON (AQP4-ON), 16 individuals with myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein-IgG-associated ON (MOG-ON), and 40 individuals with MS-associated ON (MS-ON). The authors note, “AQP4-ON eyes exhibited worse high-contrast letter acuity (HCLA) compared to MOG-ON (-22.3 ± 3.9 letters; p < 0.001) and MS-ON eyes (-21.7 ± 4.0 letters; p < 0.001). Macular ganglion cell + inner plexiform layer (GCIPL) thickness was lower, as compared to MS-ON, in AQP4-ON (-9.1 ± 2.0 µm; p < 0.001) and MOG-ON (-7.6 ± 2.2 µm; p = 0.001) eyes. Lower GCIPL thickness was associated with worse HCLA in AQP4-ON (-16.5 ± 1.5 letters per 10 µm decrease; p < 0.001) and MS-ON eyes (-8.5 ± 2.3 letters per 10 µm decrease; p < 0.001), but not in MOG-ON eyes (-5.2 ± 3.8 letters per 10 µm decrease; p = 0.17), and these relationships differed between the AQP4-ON and other ON groups (p < 0.01 for interaction).” These data indicate that AQP4-IgG seropositivity suggests worse visual outcomes than those occurring after MOG-ON or even MS-ON (Sotirchos et al., 2019).

Cantó et al. (2019) evaluated neurofilament light chain’s (NfL) ability to “serve as a reliable biomarker of disease worsening for patients with multiple sclerosis (MS).” The study included 607 patients with MS; patients were assessed over a period of 12 years. Serum NfL was measured, and disability progression was the primary clinical outcome (defined as “clinically significant worsening on the Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) score and brain fraction atrophy”). Baseline measurements of NfL showed significant association with EDSS score, MS subtype, and treatment status. Worsening EDSS scores and changes of NfL levels over time were found to be correlated. The baseline NfL measurement was also found to be associated with approximately 11.6% of brain fraction atrophy over 10 years, increasing to 18% after multivariable analysis. Furthermore, active treatment was associated with declining levels of NfL, with “high-potency treatments” associated with the greatest decrease out of all of the treatments assessed. Overall, the authors concluded that they had confirmed a significant association of serum NfL with clinical outcomes of MS. However, they also acknowledged that “further prospective studies are necessary to assess the assay’s utility for decision-making in individual patients” (Cantó et al., 2019).

Gil-Perotin et al. (2019) evaluated the combined biomarker profile of NfL and chitinase3-like1 (CHI3L1) and its ability to provide prognostic information for patients with MS. 157 MS patients were included, with 99 RRMS patients, 35 SPMS patients, and 23 PPMS patients. Disease activity was defined by “clinical relapse and/or gadolinium-enhanced lesions (Benkert et al.) in MRI within 90 days from CSF collection.” Levels of both biomarkers were found to be higher in MS patients compared to non-MS patients. Elevated NfL was associated with clinical relapse and GEL in RRMS and SPMS patients and high CHI3L1 levels were characteristic of progressive disease. The authors also found the combined profile useful for differentiating between MS subtypes, with high NfL and low CHI3L1 often indicating a RRMS stage. They found that elevation of both biomarkers indicates disease progression. Overall, the authors concluded these biomarkers were useful for disease activity and progression and that the biomarker profile can discriminate between MS subtypes (Gil-Perotin et al., 2019).

performed a meta-analysis to evaluate the CSF levels of NfL to determine “whether, and to what degree, CSF NfL levels differentiate MS from controls, or the subtypes or stages of MS from each other”. The authors identified 14 articles for inclusion in their meta-analysis. NfL levels were higher in MS patients (746) than controls (435) (mean of 1965.8 ng/L in MS patients compared to 578.3 ng/L in healthy controls). Mean NfL levels were found to be higher in 176 patients with relapsing disease (mean = 2124.8ng/L) compared to 92 patients with progressive disease (mean = 1121.4ng/L). The authors also found that patients with relapsing disease (138 in this cohort) had approximately double the levels of CSF NfL compared to patients in remission (268), with an average of 3080.6ng/L in the relapsing cohort compared to 1541.7ng/L in the remission cohort. Overall, the authors concluded that CSF NfL correlates with MS activity throughout the course of disease, that relapse was strongly associated with elevated CSF NfL levels, and that CSF NfL may be useful as a measure of activity (Martin et al., 2019).

Simonsen et al. (2020) performed a retrospective study investigating if analysis of IgG index could safely predict oligoclonal band (OCB) findings. A total of 1295 MS patients were included, with 93.8% of them positive for OCBs. Of 842 MS patients with known IgG status and known OCB status, 93.3% were oligoclonal band positive and 76.7% were found to have an elevated IgG profile. The authors found the positive predictive value of elevated IgG based on positive OCBs to be 99.4%, and the negative predictive value of normal IgG based on negative OCBs to be 26.5%. The authors concluded that an IgG index of > 0.7 has a positive predictive value of > 99% for OCBs (Simonsen et al., 2020).

Benkert et al. (2022) conducted a retrospective modelling and validation study aiming to assess the ability of serum neurofilament light chain (sNfL) to identify people at risk of future MS. The authors used a reference database to determine reference values of sNfL corrected for age and body mass index (BMI). The study included a control group (no history of CNS disease) and MS patients. In the control group, sNfL concentrations increased exponentially with age; the rate of increase rose after the age of 50. In MS patients, “sNfL percentiles and Z scores indicated a gradually increased risk for future acute (e.g., relapse and lesion formation) and chronic (disability worsening) disease activity.” The authors collected data before and after MS treatment and found that sNfL Z score values decreased to the level of the control group with monoclonal antibodies, and, to a lesser extent, with oral therapies. sNfL Z scores did not decrease with platform compounds such as interferons and glatiramer acetate. The authors conclude that “use of sNfL percentiles and Z scores allows for identification of individual people with multiple sclerosis at risk for a detrimental disease course and suboptimal therapy response beyond clinical and MRI measures, specifically in people with disease activity-free status” (Benkert et al., 2022).

International Advisory Committee on Clinical Trials in Multiple Sclerosis

In 2014, the International Advisory Committee on Clinical Trials in Multiple Sclerosis, jointly sponsored by the U.S. National Multiple Sclerosis Society, the European Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis, and the MS Phenotype Group, re-examined MS phenotypes, exploring clinical, imaging, and biomarker advances through working groups and literature searches. The committee concluded that “To date, there are no clear clinical, imaging, immunologic or pathologic criteria to determine the transition point when RRMS [relapse-remitting MS] converts to SPMS [secondary progressive MS]; the transition is usually gradual. This has limited our ability to study the imaging and biomarker characteristics that may distinguish this course” (Lublin et al., 2014). In 2020, the committee updated this policy for clarity, summarizing with “the committee urges clinicians, investigators, and regulators to consistently and fully use the 2013 phenotype characterizations by (1) using the full definition of activity, that is, the occurrence of a relapse or new activity on an MRI scan (a gadolinium-enhancing lesion or a new/unequivocally enlarging T2 lesion); (2) framing activity and progression in time; and (3) using the terms worsening and progressing or disease progression more precisely when describing MS course”(Lublin et al., 2020).

The International Panel on Diagnosis of Multiple Sclerosis

The Panel reviewed the 2010 McDonald criteria and recommended: “In a patient with a typical clinically isolated syndrome and fulfilment of clinical or MRI criteria for dissemination in space and no better explanation for the clinical presentation, demonstration of CSF-specific oligoclonal bands in the absence of other CSF findings atypical of multiple sclerosis allows a diagnosis of this disease to be made.” The Panel goes on to state that “CSF oligoclonal bands are an independent predictor of the risk of a second attack when controlling for demographic, clinical, treatment, and MRI variables” and that in the absence of atypical CSF findings, demonstration of these CSF OCBs can allow for a diagnosis of MS to be made. The Panel remarks that inclusion of this CSF criterion can substitute for the traditional “dissemination in time” criterion, but that no laboratory test in isolation can confirm an MS diagnosis (Thompson et al., 2018).

Cerebrospinal fluid examination is “strongly recommended” in some circumstances for MS diagnosis, and the Panel remarks that the threshold for additional testing should be low. Those circumstances are as follows:

- “when clinical and brain MRI evidence supporting a diagnosis of multiple sclerosis is insufficient, particularly if initiation of long-term disease-modifying therapies are being considered”

- “when there is a presentation other than a typical clinically isolated syndrome, including patients with a progressive course at onset (primary progressive multiple sclerosis)”

- “when there are clinical, imaging, or laboratory features atypical of MS”

- “in populations in which diagnosing MS is less common (for example, children, older individuals, or non-Caucasians).”

The Panel does emphasize that it is essential for CSF to be paired with another serum sample when analyzed to demonstrate that the OCBs are unique to the CSF (Thompson et al., 2018).

The treatments for these similar conditions (MS and NMOSD) differ, as some MS treatments (interferon beta, fingolimod, and natalizumab) can exacerbate NMOSDs. Therefore, the Panel recommended that “NMOSDs should be considered in any patient being evaluated for multiple sclerosis”. The Panel notes that aquaporin-4 serological testing “generally differentiates” NMOSD from MS (Thompson et al., 2018). Serological testing for AQP4 and for MOG should be done in all patients with features suggesting NMOSDs (severe brainstem involvement, bilateral optic neuritis, longitudinally extensive spinal cord lesions, large cerebral lesions, or a normal brain MRI or findings not fulfilling dissemination in space [DIS]), and considered in groups at higher risk of NMOSDs (African American, Asian, Latin American, and pediatric populations)man (Thompson et al., 2018).

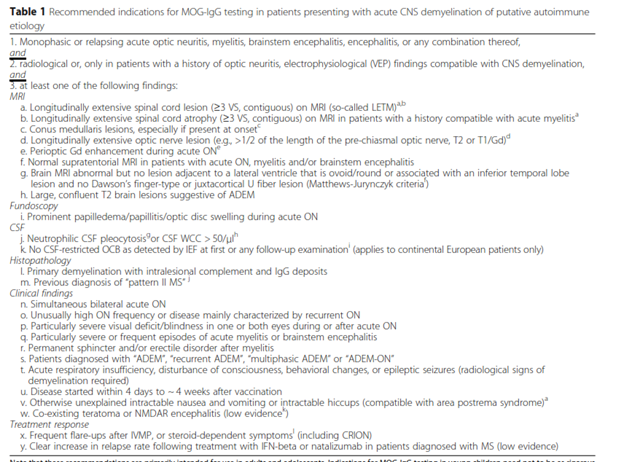

International Panel on MOG Encephalomyelitis (IPND)

Human myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG-IgG)-associated encephalomyelitis (MOG-EM) is considered a unique disease from MS and other NMOSD, but MOG-EM has often been misdiagnosed as MS in the past. In 2018, an international panel released their recommendations concerning diagnosis and antibody testing. They state their purpose with the following: “To lessen the hazard of over diagnosing MOG-EM, which may lead to inappropriate treatment, more selective criteria for MOG-IgG testing are urgently needed. In this paper, we propose indications for MOG-IgG testing based on expert consensus. In addition, we give a list of conditions atypical for MOG-EM (“red flags”) that should prompt physicians to challenge a positive MOG-IgG test result. Finally, we provide recommendations regarding assay methodology, specimen sampling and data interpretation” (Jarius et al., 2018).

They list the following recommendations:

- Assay: Indirect fluorescence assays, including fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) that targets full-length human MOG (IgG-specific), are the gold standards. The use of either IgM or IgA antibodies are less specific and can result in both false-negative results due to high-affinity IgG displacing IgM and false-positive results due to cross-reactivity with rheumatoid factors.

- Immunohistochemistry is NOT recommended because it is “less sensitive than cell-based assays, limited data available on specificity, [and] sensitivity depends on tissue donor species.”

- Peptide-based ELISA and Western blot are NOT recommended because they are “insufficiently specific, obsolete.”

- Biomaterial: Serum is the recommended specimen of choice. CSF is “not usually required” because “MOG-IgG is produced mostly extrathecally, resulting in lower CSF than serum titers.”

- Timing of testing: Serum concentration of MOG-IgG is highest during an acute attack and/or while not receiving immunosuppressive treatment. MOG-IgG concentration may decrease during remission. “If MOG-IgG test is negative but MOG-EM is still suspected, re-testing during acute attacks, during treatment-free intervals, or 1-3 months after plasma exchange (or IVIG [intravenous immunoglobulin treatment]) is recommended.”

- “Given the very low pre-test probability, we recommend against general MOG-IgG testing in patients with a progressive disease course.”

- “In practice, many patients diagnosed with AQP4-IgG-negative NMOSD according to the IPND 2015 criteria will meet also the criteria for MOG-IgG testing…and should thus be tested. However, MOG-IgG testing should not be restricted to patients with AQP4-IgG-negative NMOSD” (Jarius et al., 2018).

The table below outlines the recommendation on the criteria required for testing:

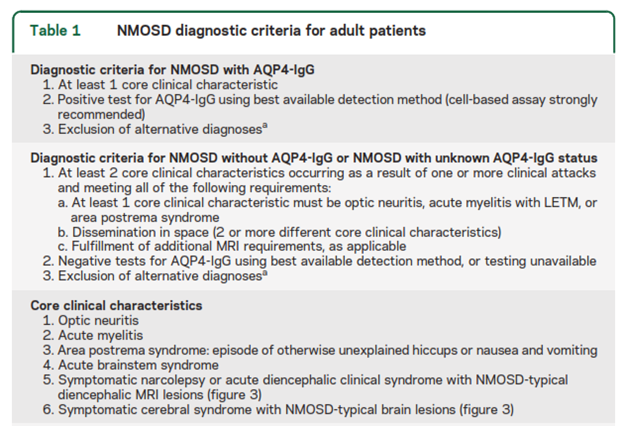

International Panel on NMOSD

The International Panel on NMOSD recommends “testing with cell-based serum assays (microscopy or flow cytometry-based detection) whenever possible because they optimize autoantibody detection (mean sensitivity 76.7% in a pooled analysis; 0.1% false-positive rate in a MS clinic cohort).” They state that ELISA and indirect immunofluorescence assays have lower sensitivity and “strongly” recommend “interpretative caution if such assays are used and when low-titer positive ELISA results are detected in individuals who present with NMOSD clinical symptoms less commonly associated with AQP4-IgG (e.g., presentations other than recurrent optic neuritis, myelitis with LETM, or area postrema syndrome) or in situations where clinical evidence suggests a viable alternate diagnosis. Confirmatory testing is recommended, ideally using 1 or more different AQP4-IgG assay techniques. Cell-based assay has the best current sensitivity and specificity and samples may need to be referred to a specialized laboratory.” The table below outlines the NMOSD diagnostic criteria for adult patients (Wingerchuk et al., 2015).

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE)

The 2022 NICE guidelines on MS in adults recommends diagnosing MS using a “combination of history, examination, MRI and laboratory findings, and by following the 2017 revised McDonald criteria” and notes that this should include “looking for cerebrospinal fluid-specific oligoclonal bands if there is no clinical or radiological evidence of lesions developing at different times” (NICE, 2022).

References

- Atlas of MS. (2023). MS Statistics. https://www.atlasofms.org/map/united-states-of-america/epidemiology/number-of-people-with-ms

- Benkert, P., Meier, S., Schaedelin, S., Manouchehrinia, A., Yaldizli, Ö., Maceski, A., Oechtering, J., Achtnichts, L., Conen, D., Derfuss, T., Lalive, P. H., Mueller, C., Müller, S., Naegelin, Y., Oksenberg, J. R., Pot, C., Salmen, A., Willemse, E., Kockum, I., . . . Kuhle, J. (2022). Serum neurofilament light chain for individual prognostication of disease activity in people with multiple sclerosis: a retrospective modelling and validation study. Lancet Neurol, 21(3), 246-257. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1474-4422(22)00009-6

- Brownlee, W. J., Hardy, T. A., Fazekas, F., & Miller, D. H. (2017). Diagnosis of multiple sclerosis: progress and challenges. Lancet, 389(10076), 1336-1346. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(16)30959-x

- Cantó, E., Barro, C., Zhao, C., Caillier, S. J., Michalak, Z., Bove, R., Tomic, D., Santaniello, A., Häring, D. A., Hollenbach, J., Henry, R. G., Cree, B. A. C., Kappos, L., Leppert, D., Hauser, S. L., Benkert, P., Oksenberg, J. R., & Kuhle, J. (2019). Association Between Serum Neurofilament Light Chain Levels and Long-term Disease Course Among Patients With Multiple Sclerosis Followed up for 12 Years. JAMA Neurol, 76(11), 1359-1366. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaneurol.2019.2137

- Comabella, M., & Montalban, X. (2014). Body fluid biomarkers in multiple sclerosis. Lancet Neurol, 13(1), 113-126. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1474-4422(13)70233-3

- Comabella, M., Sastre-Garriga, J., & Montalban, X. (2016). Precision medicine in multiple sclerosis: biomarkers for diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment response. Curr Opin Neurol, 29(3), 254-262. https://doi.org/10.1097/wco.0000000000000336

- El Ayoubi, N. K., & Khoury, S. J. (2017). Blood Biomarkers as Outcome Measures in Inflammatory Neurologic Diseases. Neurotherapeutics, 14(1), 135-147. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13311-016-0486-7

- Eriksson, M., Andersen, O., & Runmarker, B. (2003). Long-term follow up of patients with clinically isolated syndromes, relapsing-remitting and secondary progressive multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler, 9(3), 260-274. https://doi.org/10.1191/1352458503ms914oa

- FDA. (2016). 510k. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/cdrh_docs/pdf16/K161951.pdf

- Filippi, M., & Rocca, M. A. (2011). MR imaging of multiple sclerosis. Radiology, 259(3), 659-681. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.11101362

- Fryer, J. P., Lennon, V. A., Pittock, S. J., Jenkins, S. M., Fallier-Becker, P., Clardy, S. L., Horta, E., Jedynak, E. A., Lucchinetti, C. F., Shuster, E. A., Weinshenker, B. G., Wingerchuk, D. M., & McKeon, A. (2014). AQP4 autoantibody assay performance in clinical laboratory service. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm, 1(1), e11. https://doi.org/10.1212/NXI.0000000000000011

- Gil-Perotin, S., Castillo-Villalba, J., Cubas-Nuñez, L., Gasque, R., Hervas, D., Gomez-Mateu, J., Alcala, C., Perez-Miralles, F., Gascon, F., Dominguez, J. A., & Casanova, B. (2019). Combined Cerebrospinal Fluid Neurofilament Light Chain Protein and Chitinase-3 Like-1 Levels in Defining Disease Course and Prognosis in Multiple Sclerosis. Front Neurol, 10, 1008. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2019.01008

- Glisson, C. C. (2024). Neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders. Wolters Kluwer. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/neuromyelitis-optica-spectrum-disorders-nmosd-clinical-features-and-diagnosis

- Goodin, D. S. (2014). The epidemiology of multiple sclerosis: insights to disease pathogenesis. Handb Clin Neurol, 122, 231-266. https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-444-52001-2.00010-8

- Hyun, J. W., Kim, W., Huh, S. Y., Park, M. S., Ahn, S. W., Cho, J. Y., Kim, B. J., Lee, S. H., Kim, S. H., & Kim, H. J. (2018). Application of the 2017 McDonald diagnostic criteria for multiple sclerosis in Korean patients with clinically isolated syndrome. Mult Scler, 1352458518790702. https://doi.org/10.1177/1352458518790702

- Jarius, S., Paul, F., Aktas, O., Asgari, N., Dale, R. C., de Seze, J., Franciotta, D., Fujihara, K., Jacob, A., Kim, H. J., Kleiter, I., Kümpfel, T., Levy, M., Palace, J., Ruprecht, K., Saiz, A., Trebst, C., Weinshenker, B. G., & Wildemann, B. (2018). MOG encephalomyelitis: international recommendations on diagnosis and antibody testing. Journal of Neuroinflammation, 15, 134. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12974-018-1144-2

- Jitprapaikulsan, J., Chen, J. J., Flanagan, E. P., Tobin, W. O., Fryer, J. P., Weinshenker, B. G., McKeon, A., Lennon, V. A., Leavitt, J. A., Tillema, J. M., Lucchinetti, C., Keegan, B. M., Kantarci, O., Khanna, C., Jenkins, S. M., Spears, G. M., Sagan, J., & Pittock, S. J. (2018). Aquaporin-4 and Myelin Oligodendrocyte Glycoprotein Autoantibody Status Predict Outcome of Recurrent Optic Neuritis. Ophthalmology, 125(10), 1628-1637. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ophtha.2018.03.041

- Koch, M., Kingwell, E., Rieckmann, P., & Tremlett, H. (2009). The natural history of primary progressive multiple sclerosis. Neurology, 73(23), 1996-2002. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181c5b47f

- Lim, C. K., Bilgin, A., Lovejoy, D. B., Tan, V., Bustamante, S., Taylor, B. V., Bessede, A., Brew, B. J., & Guillemin, G. J. (2017). Kynurenine pathway metabolomics predicts and provides mechanistic insight into multiple sclerosis progression. Sci Rep, 7, 41473. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep41473

- Lotze, T. E. (2024). Differential diagnosis of acute central nervous system demyelination in children. Wolters Kluwer. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/differential-diagnosis-of-acute-central-nervous-system-demyelination-in-children

- Lublin, F. D., Coetzee, T., Cohen, J. A., Marrie, R. A., Thompson, A. J., & International Advisory Committee on Clinical Trials in, M. S. (2020). The 2013 clinical course descriptors for multiple sclerosis: A clarification. Neurology, 94(24), 1088-1092. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000009636

- Lublin, F. D., Reingold, S. C., Cohen, J. A., Cutter, G. R., Sorensen, P. S., Thompson, A. J., Wolinsky, J. S., Balcer, L. J., Banwell, B., Barkhof, F., Bebo, B., Jr., Calabresi, P. A., Clanet, M., Comi, G., Fox, R. J., Freedman, M. S., Goodman, A. D., Inglese, M., Kappos, L., . . . Polman, C. H. (2014). Defining the clinical course of multiple sclerosis: the 2013 revisions. Neurology, 83(3), 278-286. https://doi.org/10.1212/wnl.0000000000000560

- Luzzio, C. (2023). Multiple Sclerosis Guidelines. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1146199-guidelines

- Martin, S.-J., McGlasson, S., Hunt, D., & Overell, J. (2019). Cerebrospinal fluid neurofilament light chain in multiple sclerosis and its subtypes: a meta-analysis of case–control studies. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery &amp; Psychiatry, 90(9), 1059. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp-2018-319190

- NICE. (2022). Multiple sclerosis in adults: management. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng220/chapter/Recommendations#diagnosing-multiple-sclerosis

- Offenbacher, H., Fazekas, F., Schmidt, R., Freidl, W., Flooh, E., Payer, F., & Lechner, H. (1993). Assessment of MRI criteria for a diagnosis of MS. Neurology, 43(5), 905-909. https://doi.org/10.1212/wnl.43.5.905

- Olek, M., Howard, Jonathan. (2024a). Clinical course and classification of multiple sclerosis - UpToDate. In J. Dashe (Ed.), UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/clinical-presentation-course-and-prognosis-of-multiple-sclerosis-in-adults

- Olek, M., Howard, Jonathan. (2024b). Evaluation and diagnosis of multiple sclerosis in adults. In J. Dashe (Ed.), UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/evaluation-and-diagnosis-of-multiple-sclerosis-in-adults

- Raphael, I., Webb, J., Stuve, O., Haskins, W. E., & Forsthuber, T. G. (2015). Body fluid biomarkers in multiple sclerosis: how far we have come and how they could affect the clinic now and in the future. Expert Rev Clin Immunol, 11(1), 69-91. https://doi.org/10.1586/1744666x.2015.991315

- Rovira, A., Swanton, J., Tintore, M., Huerga, E., Barkhof, F., Filippi, M., Frederiksen, J. L., Langkilde, A., Miszkiel, K., Polman, C., Rovaris, M., Sastre-Garriga, J., Miller, D., & Montalban, X. (2009). A single, early magnetic resonance imaging study in the diagnosis of multiple sclerosis. Arch Neurol, 66(5), 587-592. https://doi.org/10.1001/archneurol.2009.49

- Sapko, K., Jamroz-Wisniewska, A., Marciniec, M., Kulczynski, M., Szczepanska-Szerej, A., & Rejdak, K. (2020). Biomarkers in Multiple Sclerosis: a review of diagnostic and prognostic factors. Neurol Neurochir Pol, 54(3), 252-258. https://doi.org/10.5603/PJNNS.a2020.0037

- Schaffler, N., Kopke, S., Winkler, L., Schippling, S., Inglese, M., Fischer, K., & Heesen, C. (2011). Accuracy of diagnostic tests in multiple sclerosis--a systematic review. Acta Neurol Scand, 124(3), 151-164. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0404.2010.01454.x

- Simonsen, C. S., Flemmen, H., Lauritzen, T., Berg-Hansen, P., Moen, S. M., & Celius, E. G. (2020). The diagnostic value of IgG index versus oligoclonal bands in cerebrospinal fluid of patients with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler J Exp Transl Clin, 6(1), 2055217319901291. https://doi.org/10.1177/2055217319901291

- Sotirchos, E. S., Filippatou, A., Fitzgerald, K. C., Salama, S., Pardo, S., Wang, J., Ogbuokiri, E., Cowley, N. J., Pellegrini, N., Murphy, O. C., Mealy, M. A., Prince, J. L., Levy, M., Calabresi, P. A., & Saidha, S. (2019). Aquaporin-4 IgG seropositivity is associated with worse visual outcomes after optic neuritis than MOG-IgG seropositivity and multiple sclerosis, independent of macular ganglion cell layer thinning. Mult Scler, 1352458519864928. https://doi.org/10.1177/1352458519864928

- Teunissen, C. E., Malekzadeh, A., Leurs, C., Bridel, C., & Killestein, J. (2015). Body fluid biomarkers for multiple sclerosis--the long road to clinical application. Nat Rev Neurol, 11(10), 585-596. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrneurol.2015.173

- Thompson, A. J., Banwell, B. L., Barkhof, F., Carroll, W. M., Coetzee, T., Comi, G., Correale, J., Fazekas, F., Filippi, M., Freedman, M. S., Fujihara, K., Galetta, S. L., Hartung, H. P., Kappos, L., Lublin, F. D., Marrie, R. A., Miller, A. E., Miller, D. H., Montalban, X., . . . Cohen, J. A. (2018). Diagnosis of multiple sclerosis: 2017 revisions of the McDonald criteria. Lancet Neurol, 17(2), 162-173. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1474-4422(17)30470-2

- Wallin, M. T., Culpepper, W. J., Campbell, J. D., Nelson, L. M., Langer-Gould, A., Marrie, R. A., Cutter, G. R., Kaye, W. E., Wagner, L., Tremlett, H., Buka, S. L., Dilokthornsakul, P., Topol, B., Chen, L. H., & LaRocca, N. G. (2019). The prevalence of MS in the United States: A population-based estimate using health claims data. Neurology, 92(10), e1029-e1040. https://doi.org/10.1212/wnl.0000000000007035

- Weinshenker, B. G. (1994). Natural history of multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol, 36 Suppl, S6-11. https://doi.org/10.1002/ana.410360704

- Wingerchuk, D. M., Banwell, B., Bennett, J. L., Cabre, P., Carroll, W., Chitnis, T., de Seze, J., Fujihara, K., Greenberg, B., Jacob, A., Jarius, S., Lana-Peixoto, M., Levy, M., Simon, J. H., Tenembaum, S., Traboulsee, A. L., Waters, P., Wellik, K. E., & Weinshenker, B. G. (2015). International consensus diagnostic criteria for neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders. Neurology, 85(2), 177-189. https://doi.org/10.1212/wnl.0000000000001729

- Yang, J., Hamade, M., Wu, Q., Wang, Q., Axtell, R., Giri, S., & Mao-Draayer, Y. (2022). Current and Future Biomarkers in Multiple Sclerosis. Int J Mol Sci, 23(11). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms23115877

Coding Section

| Code | Number |

Description |

| CPT |

83520 |

Immunoassay for analyte other than infectious agent antibody or infectious agent antigen; quantitative, not otherwise specified |

|

|

83916 |

Oligoclonal immune (oligoclonal bands) |

|

|

84182 |

Protein; Western Blot, with interpretation and report, blood or other body fluid, immunological probe for band identification, each |

|

|

86051 (effective 01/01/2022) |

Aquaporin-4 antibody; ELISA |

|

|

86052 (effective 01/01/2022) |

Aquaporin-4 antibody; cell-based immunofluorescence assay |

|

|

86053 (effective 01/01/2022) |

Aquaporin-4 antibody; flow cytometry |

|

|

86362 (effective 01/01/2022) |

Myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein antibody; cell-based immunofluorescence assay |

|

|

86363 (effective 01/01/2022) |

Myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein antibody; flow cytometry (each) |

|

|

88341 |

Immunohistochemistry or immunocytochemistry, per specimen; each additional single antibody stain procedure (List separately in addition to code for primary procedure) |

|

|

88342 |

Immunohistochemistry or immunocytochemistry, per specimen; initial single antibody stain procedure |

| 0443U (effective 04/01/2024) | Neurofilament light chain (Nfl), ultra-sensitive immunoassay, serum or cerebrospinal fluid | |

| ICD-10 |

|

|

|

|

G04.82 |

Acute flaccid myelitis |

Procedure and diagnosis codes on Medical Policy documents are included only as a general reference tool for each policy. They may not be all-inclusive.

This medical policy was developed through consideration of peer-reviewed medical literature generally recognized by the relevant medical community, U.S. FDA approval status, nationally accepted standards of medical practice and accepted standards of medical practice in this community, and other nonaffiliated technology evaluation centers, reference to federal regulations, other plan medical policies, and accredited national guidelines.

"Current Procedural Terminology © American Medical Association. All Rights Reserved"

History From 2014 Forward

| 10/09/2024 | Annual review, no change to policy intent. Updating table of terminology, rationale and references |

| 03/26/2024 | Updating policy section. Adding code 0443U (effective 04/01/2024). No other change made. |

| 10/24/2023 | Annual review, no change to policy intent. Entire policy updated for clarity and consistency.) |

| 11/10/2022 | Annual review. Updating policy for clarity, no change to policy intent. Adding table of terminology. Adding rationale, references and coding. |

| 12/8/2021 | Updating policy with 2022 coding. Adding code 86051, 86052, 86053, 86362 and 86363. No other change made. |

| 10/11/2021 | Annual review, no change to policy intent. Updating policy number, background, rationale, references and adding ICD 10 G0482. |

| 10/01/2020 | Annual review, updating policy in relation to CSF testing. Also updating regulatory status, rationale, references and coding. |

| 10/09/2019 | Annual review, no change to policy intent. Reformatting policy for clarity. |

| 09/11/2019 | Updated Category to Laboratory. No other changes. |

| 11/15/2018 | Annual review, updating title to include "related neurologic diseases". Updating policy to allow indirect fluorescence assay or FACS with medical necessity criteria. Adding investigational statements #3 and 4 in the policy. Removing CPT code 84999 from the policy. |

| 10/23/2017 | Annual review, no change to policy intent. |

| 06/13/2017 | Annual review, no change to policy intent. Updating background, description, regulatory status, rationale. |

| 06/02/2016 | Annual review, no change to policy intent. |

| 06/23/2015 | Annual review, no change to policy intent. Updated background, description, rationale and references. Added guidelines and coding. |

| 06/02/2014 | New Policy. |